How does NASA buy products? What are the challenges that the agency is facing compared to traditional commercial organizations? We spoke with Marvin L. Horne, NASA Deputy Assistant Administrator for the Office of Procurement. He told us more about how their office secures products on behalf of the space agency.

How does NASA manage its product procurement?

Marvin L. Horne: “NASA’s procurement process adheres to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, often referred to as the FAR. The FAR encompasses the fundamental framework of procurement procedures and policies for the entire U.S. federal government. It also includes standard solicitation provisions and contract clauses. Our primary approach to procurement revolves around competitive procedures. The aim is to secure the best value for American taxpayers while fulfilling our mission requirements. However, there are instances when non-competitive awards become necessary. This is tje case for unique requirements or situations where only one entity or company possesses the capabilities to meet NASA’s specific needs.”

For instance, what would constitute such an example?

Marvin L. Horne: “It could be a unique valve, one exclusively offered by a single manufacturer with ownership of proprietary data and the rights to develop, produce, and manufacture that particular item. The FAR requires single source justifications to be published on SAM.gov. Market research and posting requirements on SAM.gov enables us to reach out to a broader audience potentially interested in various procurement opportunities, whether they aspire to be prime contractors or subcontractors seeking to compete for the kinds of projects NASA has to offer. We also ensure that small businesses, women-owned, veteran-owned, and minority-serving institutions, receive an equitable share of NASA’s annual expenditure. Over the past few years, our annual spending has averaged around $19 billion. A substantial portion, roughly 80%, of NASA’s overall budget flows through the Office of Procurement as part of its expenditure.”

How do you conduct purchasing on behalf of the agency?

Marvin L. Horne: “The NASA organizational structure revolves around five mission directorates and one mission support directorate. This arrangement determines both what we procure and what types of sources may be able to provide the product or service.

- The Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate is focused on transforming aviation to make it more sustainable and more accessible.

- The Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate is dedicated to the design and development of space capabilities for the future, including projects like the Artemis Program to include the Space Launch System (SLS).

- The Space Operations Mission Directorate is responsible for enabling sustained human exploration missions and operations in our solar system. This encompasses operational entities such as the International Space Station (ISS).

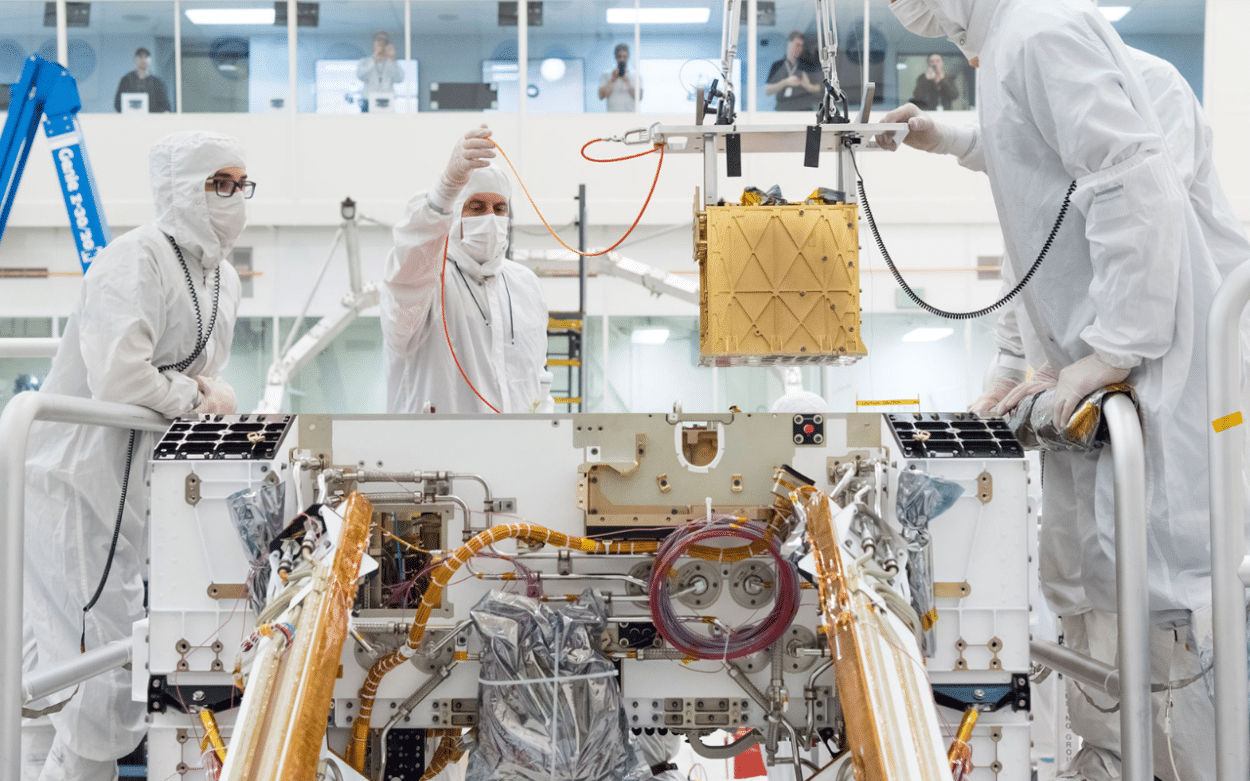

- The Science Mission Directorate (SMD) goal is to reach beyond our current knowledge by investigating the Earth, Sun, Moon, other worlds in our solar system, stars and the deep universe. Example procurements include the Mars Rovers and the DART Spacecraft.

- The Space Technology Mission Directorate specializes in the development of deep space technologies crucial for upcoming missions.

- Mission Support Directorate enables NASA mission by providing foundational support capabilities, e.g., Procurement, Legal, Financial.

Our procurement office provides support to these distinct missions through a network of 12 buying locations strategically dispersed across NASA centers. As mentioned earlier, approximately 80% of our budget flows through these 12 buying offices. In fiscal year 2022, this amounted to around $19.6 billion and involved approximately 28,000 procurement actions.”

What’s the extent of foreign product inclusion in NASA missions?

Marvin L. Horne: “NASA’s procurement practices are governed by federal acquisition regulations, which include compliance with the Buy American Act and other executive orders aimed at promoting domestic manufacturing of end products. While there is a preference for American-made products, NASA does depend on a variety of suppliers and there are instances where products are sourced from outside the United States. If it’s determined that there isn’t a domestic product available, we may explore international alternatives that align with the agency’s needs. For high-profile programs like Artemis and the SLS rocket, components are often sourced from manufacturers located across the globe. In fiscal year 2022, NASA awarded approximately $71.5 million for work conducted abroad. This work spanned 27 different countries, contributing to the Artemis program and various other NASA initiatives. We rely on an extensive network of international suppliers to fulfill these requirements, in addition to collaborating with space agencies from other nations.”

Could you provide examples of foreign companies with which NASA is conducting business?

Marvin L. Horne: “NASA does business for example with Cimel Electronique. This French company supports NASA through the Aeronet Project by supplying the sun photometers and parts necessary for the repair, upkeep, and upgrade of the sun photometers. Akira Mecaturbines is another French company that supplies the DGEN 380 engine hardware for NASA projects and missions. In addition, the Ariane Group will supply the Guipex Nozzle Material not later than the Artemis 6 (possibly earlier to increase B1B performance). The Guipex benefits is a lightweight material which enables longer nozzle construction, increasing engine Thrust and specific impulse which is a measure of fuel efficiency on rockets.”

Given that you also collaborate with other space agencies, do you sometimes find yourselves sharing the same suppliers?

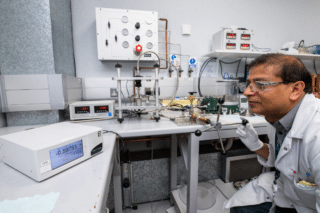

Marvin L. Horne: “Absolutely. This stems from the fact that many suppliers of human space-rated products must undergo rigorous certification processes. NASA suppliers must be ISO certified when providing flight hardware. NASA also has a stringent supply chain risk management program. NASA human rated spacecraft certifications are subject to strict engineering reviews with significant involvement collaboration with our Office of Safety Admission Assurance due to the inherent nature of high-risk space flight activities and other research and development endeavors. To produce these specialized products, companies need certifications in areas like AS9100, which establishes guidelines for Quality Management Systems. Also the application of proper parts and material is key to mission success for EEE (Electrical, Electronic, and Electromagnetic) parts. As such, there is some overlap with companies that also support the European Space Agency while simultaneously serving NASA’s needs.”

Additionally, as you collaborate more frequently with SpaceX, a private company, do they adhere to the same regulations as NASA?

Marvin L. Horne: “We engage with SpaceX for various programs, and as a result, we exercise oversight and scrutiny over the products and services they provide. This involves thorough reviews, audits, testing, and collaborative efforts not only with SpaceX but also with other providers working on missions for NASA. Our engineers and our safety and mission assurance teams conduct oversight and insight throughout the process, ultimately making final approvals in conjunction with these contractors.”

Are you utilizing online sourcing?

Marvin L. Horne: “Our approach ties back to our market research. As we all recognize, supply chains have undergone significant disruptions since the advent of COVID-19, and they are gradually recovering. Depending on the specific product, there may still be limitations in supply or increased costs. So we are contending with numerous challenges associated with supply chain management. Through market research, we continuously seek to enhance our understanding of available resources. This endeavor is not limited to procurement alone; our technical and engineering teams are also actively involved. Our engineers, who often specialize in particular disciplines or components, actively explore the industry landscape by visiting various manufacturing facilities. Industry players frequently reach out to us to showcase their latest products and innovations. We also engage in extensive outreach efforts. From a procurement perspective, we provide guidance on how to conduct business with NASA, recognizing that a significant portion of the industry may not be familiar with federal government procurement processes. These activities extend to our technical community, which collaborates with industry partners to discuss specific products and certification processes. NASA Solicitations are published on SAM.gov.”

What are the key challenges NASA faces when sourcing products?

Marvin L. Horne: “NASA encounters some distinctive challenges in sourcing products. One major difference from the commercial sector is our typically low production volume requirements. NASA does not mass-produce hundreds of SLS rockets, we manufacture only a few. These are highly specialized and unique, and their human-rated certification adds complexity to our supply chain considerations. Long lead times for procurement are also a significant challenge. Given our limited procurement volume, manufacturing companies may lack continuous production lines. For certain products, it can take a year or even longer for them to be fully assembled, tested, and ready for utilization in a mission program. This challenge ties directly to the inherent value and uniqueness of our missions. Vendor obsolescence is another issue we face. Companies may cease production of a specific valve, component, or part or upgrade it without notifying NASA. These unique challenges prompt us to explore new vendors and products and undertake rigorous testing to ensure product acceptability or certification for integrated space flight applications.”

What is currently the most challenging component to source for NASA?

Marvin L. Horne: “I’m not certain if there’s a single answer to that question. It tends to vary depending on the specific mission and the items we’re procuring. One day it could be one thing, and the situation can change over time. For example, in the immediate aftermath of COVID-19, microchips or semiconductors were challenging to obtain, but that may not be the case today. It’s a dynamic situation that ebbs and flows based on external factors, the evolving industry landscape, and shifts in the availability of certain components.”

For more information on how to do business with NASA: visit https://www.nasa.gov/office/procurement/doingbusiness