The scale of China‘s efforts to control the weather is hugely ambitious. Their effectiveness remains to be seen. From silver iodide to weather drones, let’s take a look at the various technologies that China could resort to for its meteorological masterplan.

In China, a country with a huge population that has often been ravaged by droughts and floods, efforts to control the weather date back decades.

Ever-Expanding Ambition

Since the 1950s, a series of mostly government-financed projects have attempted to enhance precipitation or suppress hail (to prevent crop damage). In 2015, China launched Tianhe (“Sky River”), the world’s largest-ever weather modification program at the time. It aimed to cover 1.6 million km2 of the vast Tibetan Plateau with a weather modification network.

Yet even the grand ambitions of Tianhe were soon dwarfed by an even greater meteorological masterplan. In December 2020, Beijing announced that its efforts to modify the weather would be ramped up across 5.5 million km2. This is 60% of China’s total land area.

For Sofya Bakhta, an analyst with China-based market research and consulting firm Daxue Consulting,

“Beijing wants to modify China’s weather to address two key issues – food security and extreme weather. The goal is to have a nationwide weather system in place by 2025, and to acquire ‘advanced weather modification skills’ by 2035.”

Silver Iodide for Cloud Control

Attempting to control the weather is now a global endeavor, with programs to control precipitation currently in operation in over 50 countries. Since the discovery in the late 1940s that crystals of silver iodide can form ice crystals in water vapor, meteorological scientists have been working to understand how to control the way water forms and moves within a cloud.

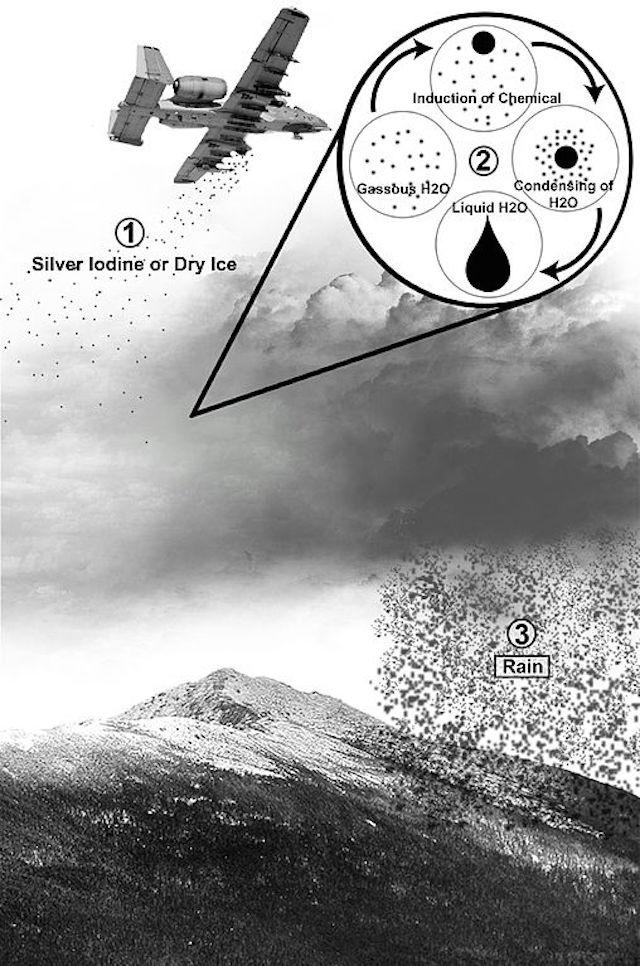

China’s new weather modification masterplan will largely rely on “seeding” clouds, a process which attempts to produce rain or snow by artificially adding condensation nuclei (e.g. silver iodide) to the atmosphere, providing a base on which snowflakes or raindrops can form.

Yet despite decades of research, there is still considerable skepticism surrounding cloud seeding. This is partly because analyzing the efficacy of this technique is a hugely challenging proposition, according to Bart Geerts, Professor of Atmospheric Science at the University of Wyoming. Geerts has co-authored more than 20 peer-reviewed papers on cloud seeding over the last decade.

“You need decades of storm data to statistically assess impact, and funding agencies (private or government) simply can’t afford to wait that long.”

In recent years, Geerts and his research partners have tried to quantify the impact of more targeted silver iodide seeding on supercooled liquid clouds using aircraft and quantifying precipitation using radar. They have found that in some conditions, modest amounts of snow can be produced, but only when naturally occurring precipitation is minimal.

“This effect can be scaled up of course, as the Chinese government intends to do, using many more silver iodide seed generators over many storms across the season. The problem is, supercooled liquid clouds that do not naturally produce snowfall are rare.”

Beyond Silver Iodide—Electricity

Cloud seeding has traditionally been carried out by dispersing compounds such as silver iodide into clouds. As yet, published scientific literature shows no environmentally harmful effects from cloud seeding with silver iodide aerosols. But there is still growing concern about pollution as silver is one of the most toxic heavy metals, particularly to aquatic life.

Fallout from cloud seeding with silver iodide is not always restricted to local precipitation and silver is sometimes detected several hundred kilometers downwind of seeding events.

Scientists have therefore started to look for new and more environmentally friendly ways to induce precipitation. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), for example, has funded research at the University of Reading in the UK, where meteorologists have developed a cloud seeding technology based on electricity.

A research team at the university’s department of meteorology discovered that when cloud droplets have a positive or negative electrical charge, the smaller droplets will combine to form bigger raindrops. The size of the raindrops is critical, because in hot places such as the UAE, with an average annual rainfall of just 100mm, small drops normally evaporate before they reach the ground.

Dr. Keri Nicoll is coordinating the research:

“What we are trying to do is to make the droplets inside the clouds big enough so that when they fall out of the cloud, they survive down to the surface.”

Catapult-launched, custom-built drones with a two-meter wingspan are now being tested in the UAE to deliver electric charges to clouds. These fly at low altitudes, with sensors measuring temperature, charge and humidity.

Weather Drones

China itself is also testing weather drones, although as yet these are launching conventional rainmaking payloads – usually powdered silver iodide – into the clouds.

Ganlin-1 (Ganlin means “sweet rain” in Chinese), the country’s first weather modification unmanned aerial vehicle, carried out its maiden flight in January 2021. In addition to its cargo of rain-seeding chemicals, it is also equipped with an array of weather sensors. With a range of 5,000 km, it can fly into geographically remote areas to test weather conditions and it automatically adjusts its flight path to maximize seeding impact.

Yu Yong, deputy head of the China Meteorological Administration explains:

“Cloud seeding with drones such as Ganlin-1 potentially offers a big improvement over land-based seeding or seeding with airplanes. Not only is it cheaper, more targeted and more flexible, we can also use drones to analyze the effects of seeding, allowing us to make refinements to the process.”

China’s innovation in weather control doesn’t stop at drones. Researchers from Tsinghua University in Beijing have experimented with the use of low-frequency sound to increase rainfall. According to scientists, sound waves emitted by acoustic cannons can “excite” clouds, leading to a greater probability of water particles aggregating.

The team says a test in 2020 saw rainfall increase by as much as 17%. But according to Professor Andrea Flossmann of the University of Clermont Auvergne in Clermont-Ferrand, France, most international weather experts remain unconvinced.

“To date, both acoustic cannons and short-pulse lasers have not been shown to have any meaningful effect on precipitation.”

Future Success?

How successful China will be in controlling its weather remains to be seen. Despite this uncertainty, many of China’s neighbors are already concerned about the possible impact of Chinese weather modification efforts on their own weather systems. Besides, weather modification technology is still largely unconstrained by international legislation. In India, China’s plans have been described as a serious threat that could lead to international conflict.

Most cloud seeding experts, however, agree that it is far too early to be alarmed. Arthur Rangno, a former member of the University of Washington’s Cloud and Aerosol Group, says:

“I would not have the least concern over what China is doing since I’m pretty dubious about all of their efforts. In my opinion they are probably having little effect, except employing a lot of people.”