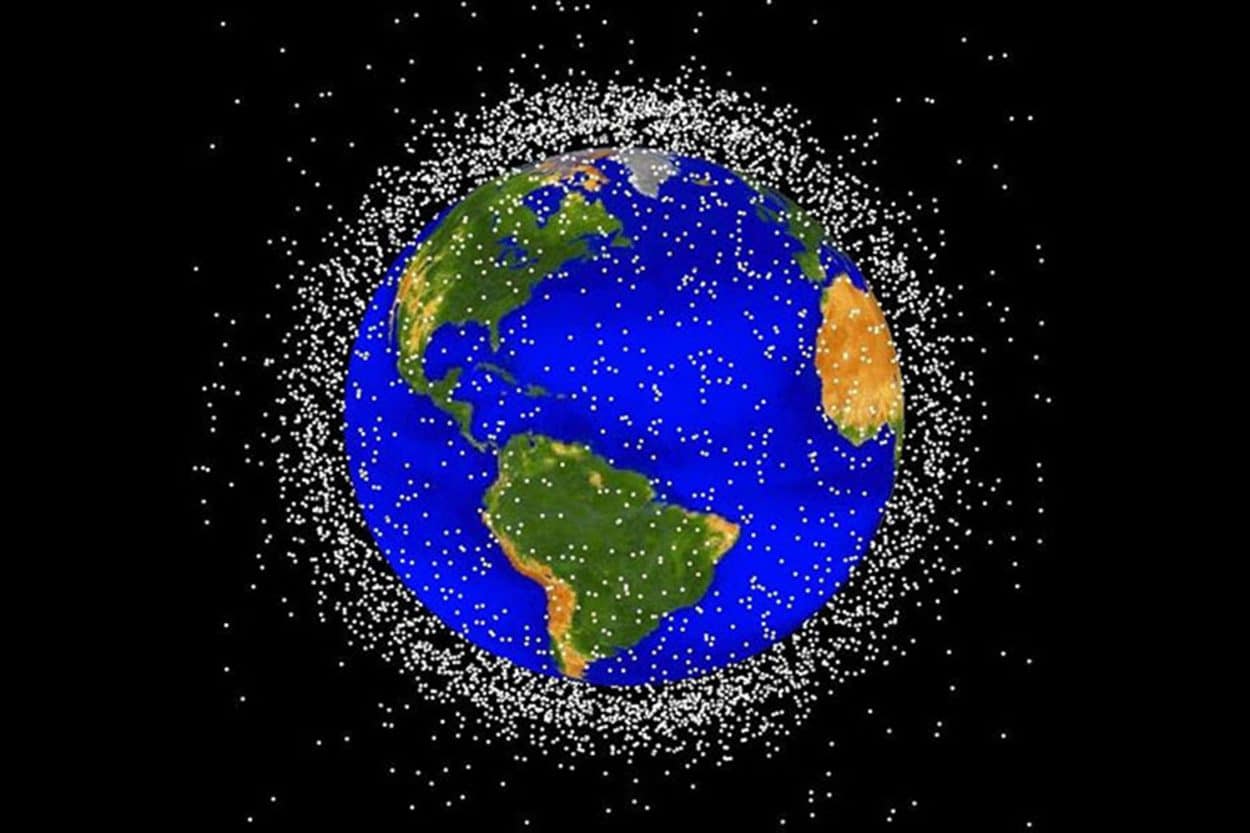

By grabbing abandoned satellites with a giant claw and flinging them back to Earth so they burn up in the atmosphere, Clearspace aims to address the growing threat that orbiting junk presents to the burgeoning space industry.

Over 60 years of space exploration has left more than 160 million pieces of space junk in Earth’s orbit. Travelling at average speeds of 28,000 kmh, this debris poses a significant threat to satellites and spacecraft.

Swiss start-up ClearSpace SA has signed an €86 million deal with the European Space Agency (ESA) to start cleaning up dangerous space junk. Equipped with a large four-arm claw, ClearSpace-1 is designed to autonomously rendezvous with objects in orbit, capture them and shift them to a lower orbit where they will burn up in a specified reentry window.

Due to launch in 2025, ClearSpace-1’s first target is a 113 kg Vega Secondary Payload Adapter (VESPA) which has been in orbit since 2013. Clearspace CEO and co-founder Luc Piguet explained:

“ESA gave the European space industry a list of 20 objects in orbit which are a problem and invited mission proposals with costings as well as a business plan for the future of in-orbit servicing. We chose VESPA as our first target because its simple design reduces risk when capturing it, but we’re doing a lot of work with machine learning to determine the exact orientation, rotation and speed of space junk – which will allow us to grapple with more awkwardly-shaped objects tumbling in space.”

ClearSpace spun out of EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) university in 2017. Some members of the ClearSpace team had worked on the 2009 SwissCube-1 launch. In 2012, the team began developing an academic mission to deorbit the cubesat in order to establish the feasibility of dealing with space junk. Mr. Piguet explained:

“The SwissCube launched directly into the debris field of the Kosmos-Iridium satellite collision, which meant we regularly received warnings about possible collisions. We realized that our little satellite was perhaps more at risk of dying from a collision than from component failure, so we started studying the challenges of capturing space junk – as it’s much easier to deorbit large objects, rather than after they disintegrate into deadly fragments which are impossible to track.”

While ClearSpace-1’s baseline is a single-use mission, the goal is to develop a reusable craft to further reduce the cost of removing dangerous objects from orbit.

Industry demand for the ability to remove or repair satellites is set to grow, with OneWeb announcing plans to expand its constellation to 2,000 satellites, while Amazon’s Project Kuiper plans to launch a constellation of 3,236 satellites.

As the cost of launching satellites falls it is becoming more economical to create vast constellations, but the trade-off is that launching states are liable for more objects in orbit. Pressure is growing for these satellite operators to address congestion in orbit rather than simply abandon satellites, Piguet says.

“Satellite operators are already expected to detail their deorbit strategy when applying for Launch Operator Licenses, in order to reduce the risk posed by space junk. Disposing of satellites could even become a built-in ‘sustainability’ component of license costs, similar to carbon offsets or other fees designed to tackle the environmental impact of products and services. These costs could be neutral on the cash flow of the operator, by passing this overhead along.”

The rise of providers like ClearSpace, Japan’s Astroscale and the United States’ Orbit Fab is set to drive a new “in-orbit services” industry – offering the ability to refuel, repair or deorbit satellites.

Traditionally, most satellites have not been designed to be easily retrieved because it was not technically or economically feasible to do so. This is changing with new initiatives : for example, OneWeb is incorporating docking plates into its satellites to make them easier to capture in orbit.

Once satellite operators can better manage the lifespan of their satellites, Piguet says it will pave the way for new business cases and new industries.

“It’s just like how the rise of motor vehicles spawned a range of new service providers such as tow trucks, petrol stations and motor mechanics – which in turn influenced the design of vehicles to make them more easily serviceable. We don’t abandon cars to rust in the middle of the road just because they’ve broken down, nor do we need to abandon satellites cluttering up orbit when they need to be repaired or removed.”